Courtauld Gallery, Somerset House

Annabel Dover had mentioned in my tutorial that I should see Peter Lanyon’s Soaring Flight exhibition whilst in London. I arrived soaked through having walked from the Euston Road, my favourite time to see London being in the early morning, before it rouses.

A number of rooms guide you to the Lanyon gallery. Matthew Smith’s Lilies in a Jar, 1913, caught my eye for three reasons.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/arts/yourpaintings/paintings/lilies-in-a-jar-207474

I am interested in flower paintings by notable artists as they affirm it is OK to paint everyday subjects; I wasn’t familiar with his work; and, following on from our making day, where Caroline had been testing decorative backgrounds against her eggs, I was struck by the decorative background in Smith’s work, which I would normally have considered to be competing with the subject. The Courtauld quote him as saying that he wanted ‘to create something as living as nature, so that it itself may continue to live.’ Some research and reflection required.

More flowers from a master, an early Picasso Yellow Irises, 1901.

In the same room a young girl with melancholy eyes caught my attention.

Chaim Soutine, Young Woman in a White Blouse, 1923 http://www.carollyne.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/IMG_2901.jpg

Such emotion from this Russian artist, a prolific painter of portraits and carcasses, amongst other subjects.

More emotion, this time from the manner in which the paint is applied. Leon Kossoff painted Christ Church, Spitalfields on many occasions, this version was 1992. The energy, the urgency and the angst is palpable. https://40.media.tumblr.com/18cf718056c313d7893299b59e30f2fb/tumblr_nnibhivvbt1suuc8do1_500.jpg

https://40.media.tumblr.com/18cf718056c313d7893299b59e30f2fb/tumblr_nnibhivvbt1suuc8do1_500.jpg

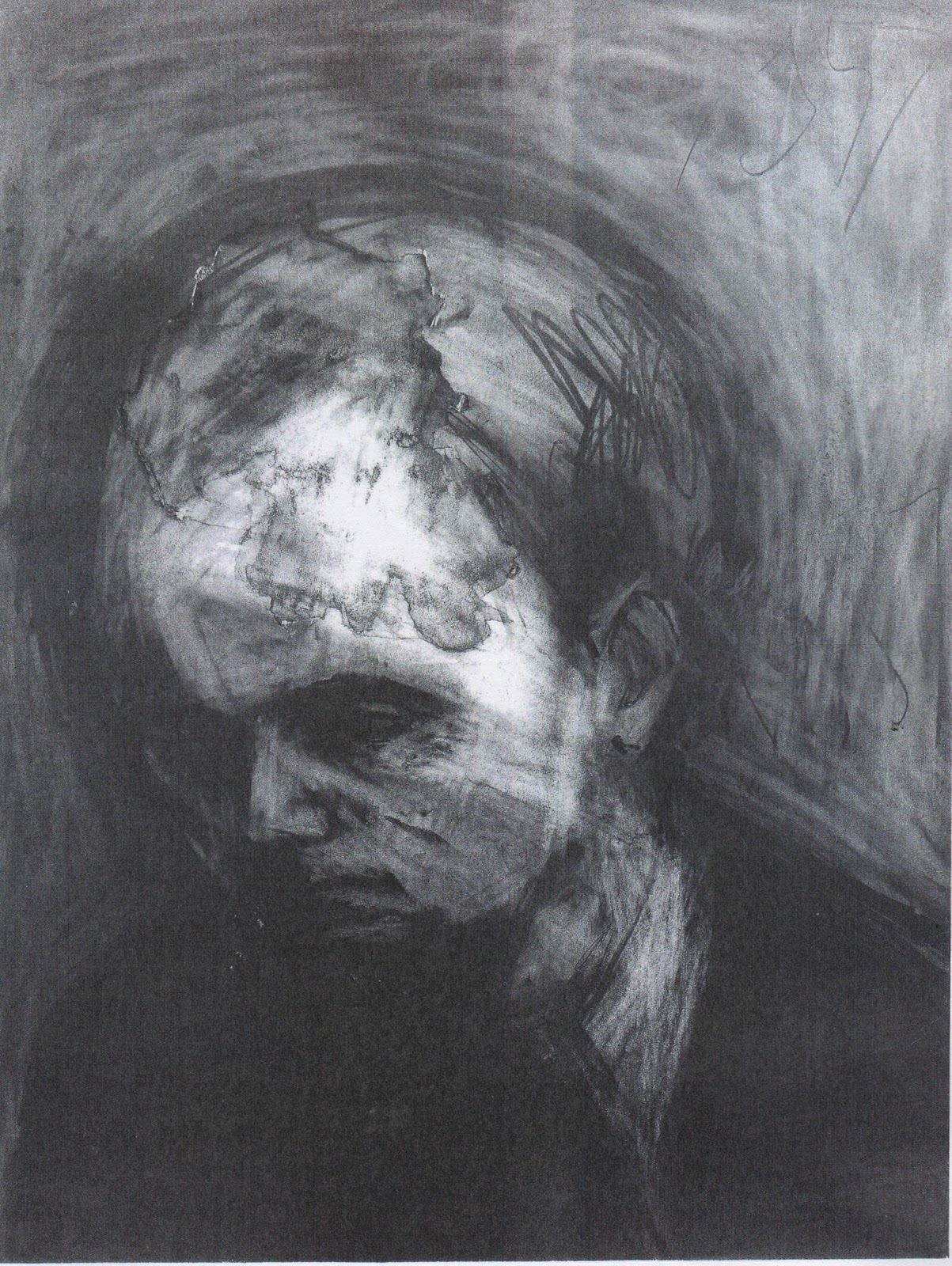

The same energy and use of impasto is also evident in an earlier work, Head of Speedo 1964.

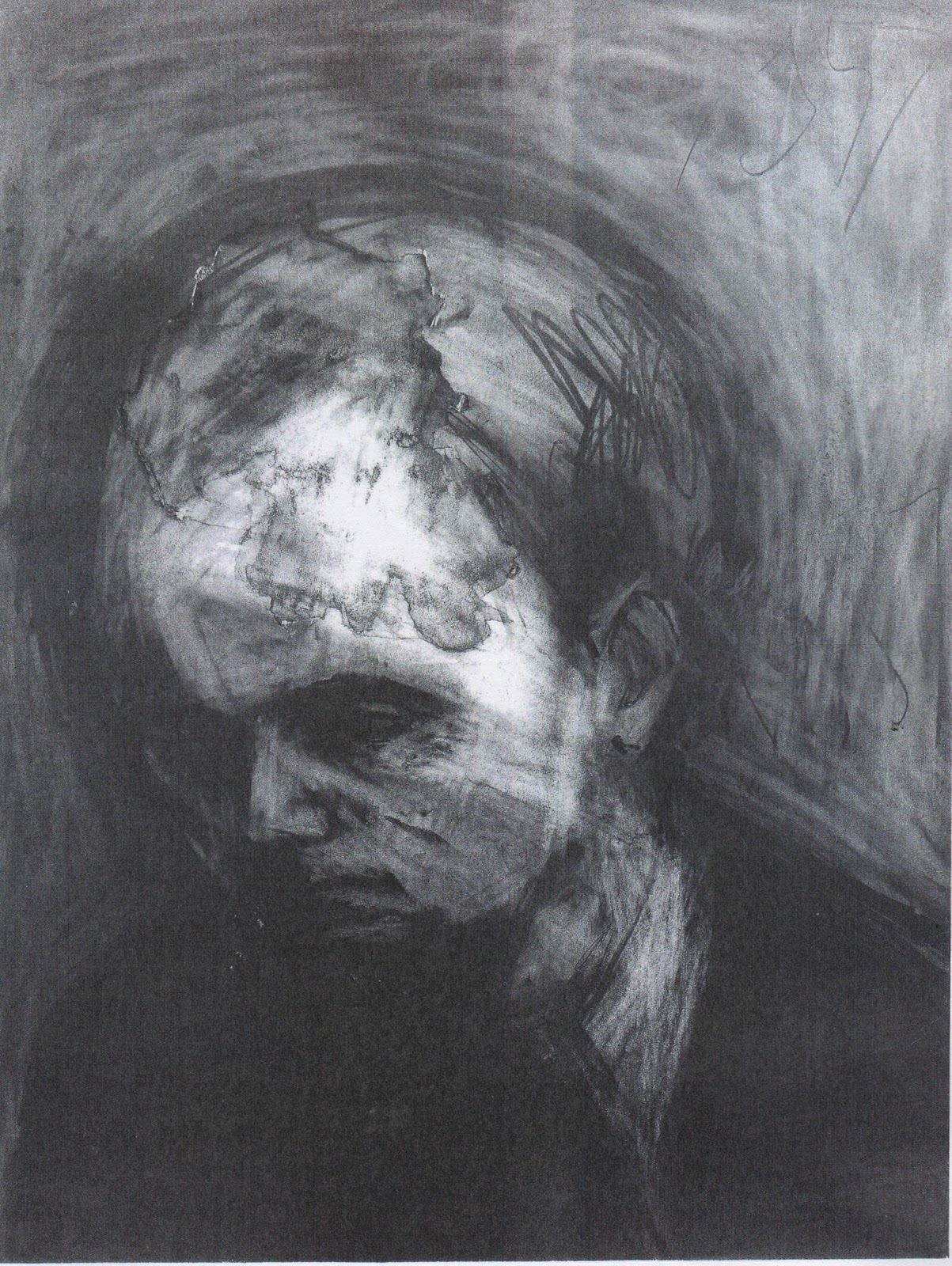

Frank Auerbach, Head of Leon Kossoff, 1957 https://lh6.googleusercontent.com/-pWIYAm61Roo/TXOZNpFsj5I/AAAAAAAAAQQ/wtO5KmDC0c8/s1600/Image+%252824%2529.jpg

Auerbach’s immense energy is woven into this charcoal drawing, where trace evidence of passionate reworking, leaves you in no doubt of his determination to capture the very essence of Kossoff.

Kossoff and Auerbach were students of David Bomberg’s evening classes at the Borough Polytechnic. Bomberg’s passion and belief in the fundamental importance of form is evident in his students’ work.

Finally I make it to Soaring Flight, an exhibition of Peter Lanyon’s gliding paintings. Initially I am reminded of the landscapes of Richard Diebenkorn, the use of colour, the perspective, but these works offer more. Painted from the perspective of the pilot, they are a journey through his emotional responses to the challenge, the thrill, the turbulence, that was finally to tragically take his life in 1964, at the age of 46.

Thermal, 1960 http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2015/oct/25/peter-lanyon-soaring-flights-review-courtauld-rhapsodies-in-blue

Cornish born, a member of the Penwith Society of painters in St Ives, which included Patrick Heron, Terry Frost and Roger Hilton, he flew off his native West Cornwall coast, naming the works after gliding terms.

Soaring Flight, 1960 photograph: Courtesy of Arts Council Collection

Lanyon took up gliding in 1959. Already a successful painter, gliding took his work to another level.

These works are Lanyon’s emotional response to the sensation of letting go, to confronting his demons, to just being free. The Courtauld references ”a sense of breathlessness and attitude of wonder’, akin to seeing a woman naked.’

They are a unique and remarkable body of work, that succinctly convey the viewer into Lanyon’s almost spiritual world.

Glide Path, 1964 http://www.telegraph.co.uk/art/what-to-see/peter-lanyons-gliding-paintings-courtauld-review/

Solo Flight, June 1960 Credit: Scottish National Gallery of Art Edinburgh

Tate Modern – Making Traces

That word again, how could I not go.

I have been looking at the work of Lee Krasner and I think this is the first work I have seen in the flesh. Gothic Landscape, 1961 was painted five years after the sudden death of her husband, Jackson Pollock, it is one of a series of gestural paintings, whose emphatic brushstrokes reflected her grief.

Gothic Landscape 1961 Lee Krasner 1908-1984 Purchased 1981 http://www.tate.org.uk/art/work/T03291

The next room was dedicated to Rebecca Horn, a deeply committed artist, whose work I don’t yet understand. (Some background to her work http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2005/may/23/art)

The House of Pain 2005

The House of Pain 2005

Gestural fingertip mark making with crayon marks from her pencil mask.

American artist Amy Silman is another artist I have yet to research. Her canvas Clubfoot 2011, clearly shows the history and subtlety of her mark making, which draws you into her work.

American Mark Bradford’s Riding the Cut Vein 2013 is a huge work, collaged from scraps of posters found in the area depicted, a contemporary take on the work of de la Villegle, which is shown alongside.

a closeup of the right hand section. His paintless process builds layer upon layer of process and material history.

a closeup of the right hand section. His paintless process builds layer upon layer of process and material history.

Details from his recent exhibition at the White Cube. http://whitecube.com/exhibitions/mark_bradford_through_darkest_america_by_truck_and_tank_bermondsey_2013/

German artist Gerhard Richter, whose work I really like for its tactile sensitivity on a grand scale, had a single room with four of his large scale paint and scrape works, showing the history of marks, movement and gestures.

Unlike to sensation I experienced in the room dedicated to Lanyon’s aerial views, where I felt I was silently gliding with the artist, in Richter’s room, the collective works felt like smothering, rather than uplifting.

The final work that caught my eye in this huge exhibition of nine rooms was a small abstract photograph by American Brett Weston.

He works from nature to capture that that we miss. I thought this image was Chinese calligraphy, but is in fact tree bark.

A behinds the scenes view of the exhibition http://www.tate.org.uk/context-comment/video/making-traces-tateshots

This exhibition was brilliant in its conception and presentation of the various meanings of this word. There is so much more to be seen than I have mentioned. So much to reflect on and ideas to be taken into my work.

On the way back to the station I popped into the Bankside, which stands in the shadow of Tate Modern, and chanced upon this arresting woodcut Golden Girl 120 x 120cms, by Laura Rosser.

http://printmakerscouncil.com/artist-page/?artist=laura-rosser

It reminded me of a photo I took in Cornwall a few years ago and how I might transform the image.

I am not sure I achieved my objective of improving my critiquing skills, but I now have first hand experience of the power of emotion in painting, and the sensitivity that traces can bring to work. An amazing day.

.jpg)